The 2023 American Birding Association’s Bird of the Year: the Belted Kingfisher.

Megaceryle alcyon

A special thank you to Marina Richie for inspiration!

Upper Deschutes Queenfisher in the snow storms of March 2023

Every now and then you encounter a bird with whom, for whatever reason, you develop a personal relationship. Sometimes it is a bird you rescue, perhaps it is an individually recognizable bird who visits your feeder, or maybe it is a bird which seems to be around during a special or hard time in your life. This winter, our family developed a relationship with a Queenfisher, technically known as a female Belted Kingfisher.

The relationship began last November as winter moved in. We were reading Marina Richie’s book Halcyon Journey: In Search of the Belted Kingfisher. Entranced by Marina’s poetic writing and intrigued by her literary love affair with this deceptively secretive bird, we set out to better know our local kingfishers. Marina helped us realize we had taken kingfishers for granted. They may be loud and perch in full view, but they let few get close and hardly any find out their secrets.

Queenie scolding

As if she knew our purpose, the Queenfisher immediately scolded us when we reached the riverside. Her call, often described as a harsh rattle, left us duly chastised for taking so long to fully appreciate such an amazing creature in our midst. We also knew she was warning us to stay far enough away to let her fish in peace.

‘Our’ Queenfisher lives year round on the Deschutes south of Sunriver. Many female kingfishers migrate, but this one does not.

Queenie on ‘her’ bridge

She spends the year on a stretch of the Deschutes near a concrete bridge where we have visited her almost daily for several months; we think she believes the bridge is hers. When she really wants her opinion considered, she has perfected the use of the bridge to echo her voice such that it reverberates for quite a distance. We can’t help but wonder if this is not an adaptation to traffic and other human noise.

Belted Kingfishers are common in the Upper Deschutes and across the continental United States. In fact, Cornell’s Birds of the World says they are “one of the most widespread land birds in North America.” Yet, according to the same source, they are “poorly studied.” Fortunately, Marina’s book is an incredible and deep source of information about this fascinating, yet little known, species. Not only does Marina cover the available technical details, but she adds to what is known with her own observing, wondering, and discovering.

Juvenile Belted Kingfisher in Bend

The North American Belted Kingfisher is part of large worldwide bird family, Alcedinidae, of about 120 species. They are so widespread that one fun podcast host pointed out that if you develop a kingfisher phobia and decide you must live where you could not encounter one, you would have to move to one of the poles or the Sahara desert! https://www.scienceofbirds.com/podcast/kingfishers.

In North America, there are approximately 1.7 million breeding Belted Kingfishers. This may sound like a lot, but sadly their population has decreased by at least a million birds from their estimated population in 1970.

Like so many other creatures and plants, Belted Kingfishers need clean clear water to feed.

Elk crossing the shallow center of the Upper Deschutes in the winter when many stretches are only a couple of feet deep

Such waterways are vanishing, even here in the Upper Deschutes. Due to drought conditions, the Deschutes River cannot meet the water needs of people downstream. From around October to April, the river is now only a couple of feet deep in many places around us.

As a result, one night of freezing temperatures can ice over the kingfishers’ feeding areas. During warmer seasons, turbidity is a serious issue. When Wickiup was low these past two years, the Upper Deschutes became thick with muddy silt and algae began growing over the oxbows. Dead fish washed up on the river banks around Sunriver and the kingfishers could not see their prey. No one has studied how many kingfishers we lose during these times.

Every day this winter when we woke to a frozen river, we anxiously hiked out to see if Queenfisher (nicknamed Queenie by my youngest) was okay. We’d look for her on her favorite morning perch, but she was not there. We have no idea where she goes when there are no fishing holes. We hiked up and down the river looking for her.

Pied-billed Grebe fishing in the only open water left in Queenie’s stretch of the river on a chilled morning in February

We only found a couple of holes in the ice and those were full with geese, ducks, otters, and even a Pied-billed Grebe.

And, none of the openings were near perches for Queenie because they tend to be out in the middle of the river where the water flows a bit faster. Fortunately, the river usually thaws in a day or two and Queenie has somehow survived each freeze so far. As soon as the river breaks up, she reappears and starts pulling fish.

Belted Kingfishers are piscivorous, which is a cool term for primarily fish-eating. Apparently they will sometimes grab some other small creatures, but we have only seen them eat fish. Watching Queenie feed is amazing. She dives into the water like a bullet. She usually dives from her perch, but occasionally she will hover over the river briefly before the final plunge. Somehow she pulls back up and out of the water without fully submerging. We can’t see what happens under the water, but we learned that she likely grabs the fish rather than stabs it. Certainly, when she emerges the fish is in her bill, not impaled.

Queenie taking a fish up to her favorite perch to give it a good smash

Whatever she does down there, it is effective because she almost always succeeds and her catches are often more than twice the length of her head! She then goes back to her perch and smashes the fish against the branch a couple of times before she aligns it head down her throat and swallows it whole.

We also learned kingfishers regurgitate pellets to manage the undigestible fish bones.

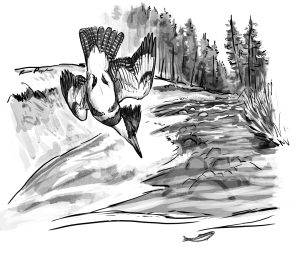

Illustration by Ram Papish

Speaking of bullets, a Japanese engineer was inspired by kingfishers when he designed one of the high speed ‘bullet’ trains. This story of biomimicry to solve an engineering problem is really interesting. My kids enjoyed this version: https://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/p074bhmx. We have never looked at a kingfisher bill in the same way since we listened to this program.

And speaking of otters, researchers think the U.K. Common Kingfisher sometimes teams up with river otters as a way to improve fishing success. https://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/p0bhy3c4. Our family’s unscientific kingfisher observations lead us to believe our Central Oregon kingfishers might have also figured out the otter thing. We often notice kingfishers around otters and we recently watched a kingfisher follow a pair of otters up a tributary as they all fished. Could be coincidence, but it is fun to wonder.

A few of Queenie’s many poses

Not just because of her impressive bill, Queenie is handsome. We love watching her lift and lower her chic crest while fanning her starry-night wings and tail. Like all female Belted Kingfishers, Queenie’s charcoal necklace arcs down to a rust-rouge waistcoat. For those who remember Marlene Dietrich in her dark suits with white shirts and red scarves, we have to ponder if the Belted Kingfisher inspired her defiant style! Male Belted Kingfishers grow out of their rust band, maturing into a pure grey and white look. Marina’s book wonderfully delves into why kingfishers’ plumage coloring defies gender stereotypes.

Male Belted Kingfisher in Bend

Around the end of February, we noticed a male Belted Kingfisher appear downstream. So far, he stays four river bends away, but we suspect he can hear Queenie from there. According to Birds of World, Belted Kingfishers are seasonally monogamous. We checked our last two years of bird lists and noted Queenie has been alone on her stretch of the river all winter for the last several years until a male turns up in late February. Could the downstream guy be the same one from last year? Thanks to Marina’s compelling accounts of watching Belted Kingfisher courtship, we are inspired to pay more attention this year.

Male Belted Kingfisher

Our bird records show that after Queenie was joined by a male, they hung out together for a while and then we only saw one at a time for a period in the spring. We have to assume this was during egg incubation. But where did Queenie and her seasonal husband nest? Belted Kingfishers nest in earthen burrows which are usually above the waterway. They dig the burrows themselves using their bills and toes. Some burrows can be up to fifteen feet long! One of our favorite parts in Marina’s book is where she discovers ‘her’ kingfishers diving into a bank using their bills as battering ram excavators.

Illustration by Ram Papish

This Belted Kingfisher behavior had never been documented in scientific literature before, so Richie’s discovery ended up being cited in an ornithological research paper. We appreciated how a naturalist’s love of a bird inadvertently ended up contributing to science. https://marinarichie.com/2022/06/23/kingfishers-why-we-need-a-naturalist-renaissance/.

Illustration by Ram Papish

The more we learn about Queenie, the more connected we feel to her. The kids get excited to go out and say hello to her and worry when she is not on her usual perch. This stretch of river would not feel right without her commanding call declaring she belongs here as much as the towering ponderosas. Queenie’s ancestors appear in the stories and traditions of the tribes who fished alongside these birds back when the river flowed evenly and clear. Before it was dammed, the Deschutes River was known as one of the most stable rivers in the world with unusually consistent spring-fed water levels. https://www.deschutesriver.org/how-to-help/raise-the-deschutes/where-does-our-water-come-from/. Marina Richie’s book illustrates how kingfishers touched the imaginations of so many different tribes in her overview of Native American Kingfisher stories. So, my kids are far from the first generation to sit on the banks of this river connecting to a kingfisher. Let’s just hope they are not the last.

The Belted Kingfisher is the 2023 American Birding Association’s Bird of the Year. https://www.aba.org/belted-kingfisher-the-2023-aba-bird-of-the-year/. For identification and scientific details see https://www.allaboutbirds.org/guide/Belted_Kingfisher.

SAVE THE DATE – May 24, 2023

On May 24th, the Sunriver Nature Center celebrates one of our coolest and most handsome waterway birds and the American Birding Association’s Bird of the Year: the Belted Kingfisher!

A bird that inspired a Japanese bullet train design, is related to the Australian Kookaburra, and smashes its head into cliffs to build nests!….Yes, and there is so much more to learn and enjoy about kingfishers…

So join us for a kingfisher themed afternoon of outdoor and indoor kids’ activities followed by an all ages evening walk and talk led by Marina Richie, author of Halcyon Journey, In Search of the Belted Kingfisher.

Marina Richie’s book will be on sale at the Nature Center gift store and our local Sunriver Books and Music https://www.sunriverbooks.com/.