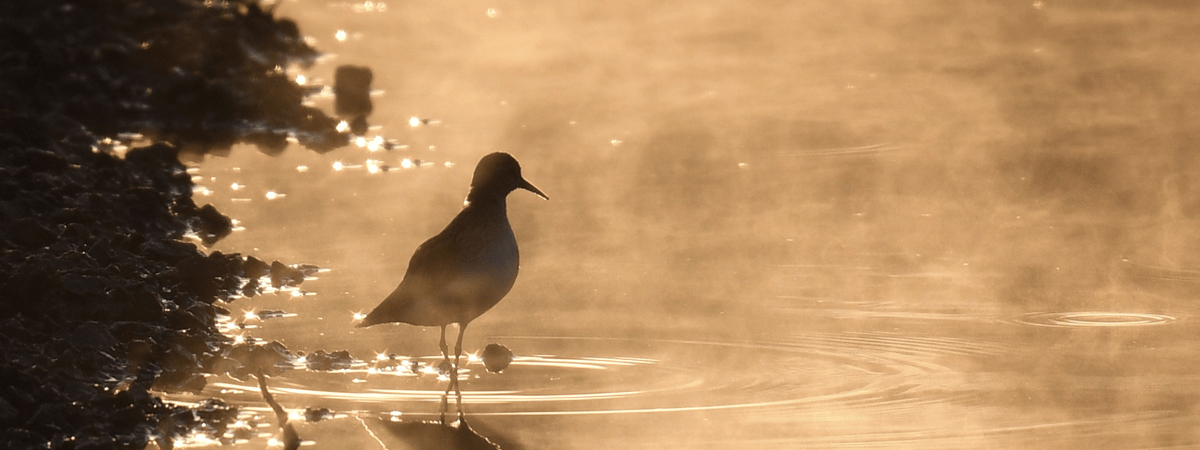

A migratory shorebird foraging for food in a Sunriver area sewage pond during a September 2022 Cedar Creek Fire smoke event.

By Sevilla Rhoads, including a conversation with Dr. Olivia Sanderfoot

Introduction

Like so many others in Central Oregon, our family spent many days sitting inside these past two months listening to droning air filters. We constantly checked the AQI readings. In the Sunriver area, there were days when the air quality reached the “purple” hazardous level. During those times, a red sun barely shone through the dark gray fog which shrouded our homes.

Unable to bike, walk, or play outside, we felt sorry for ourselves. Then we saw a bird staggering across the driveway. Lethargic and disheveled, the bird started to open its wings to fly but appeared to give up. It dropped its head and shuffled under the shelter of a parked car where it sat, motionless with eyes half closed. As we looked around, we saw several other birds hunched under shrubs and feeders.

Was the smoke harming the birds? We realized we needed to learn how wildfire smoke impacts wild birds. As I watched a chickadee, sitting motionless in the eerie orange, gray light of another smokey morning, the idiom “canary in a coal mine” came to mind.

Until around 1986, miners, while underground, carried caged canaries. If the canary suddenly stopped singing or became sick and died, the miners would leave and check for poison gasses. Why were canaries used as gas detectors? We looked it up.

Smithsonian Magazine says birds are early detectors of dangerous gas because they are so vulnerable to airborne poisons: “Because they need such immense quantities of oxygen to enable them to fly and fly to heights that would make people altitude sick, their anatomy allows them to get a dose of oxygen when they inhale and another when they exhale, by holding air in extra sacs…. Relative to mice or other easily transportable animals that could have been carried in by the miners, they get a double dose of air and any poisons the air might contain, so miners would get an earlier warning.” https://www.smithsonianmag.com/smart-news/story-real-canary-coal-mine-180961570/

If birds are so sensitive to poisonous gas that they were used as detectors, what is the impact of wildfire smoke? We decided to look into current research on wildfire smoke and wild birds. Quickly, we noticed most relevant articles quoted or referred to the same researcher, Dr. Olivia Sanderfoot. We noted she recently conducted her research from Seattle, so she is familiar with Northwest birds. Not expecting a busy scientist to respond but feeling this topic was too important not to try, we reached out to Dr. Sanderfoot with our questions.

Not only did Dr. Sanderfoot reply to our email, but she took the time to call and agreed to let us post a summary of our conversation. She generously gave up precious time in her super busy schedule to help us better understand this critical topic for anyone interested in Western U.S. birds.

As a layperson without any scientific training, I was worried I would get lost when Dr. Sanderfoot explained her research and theories. However, her articulate replies were clear and easy to follow. And, while she carefully walked me through the topic’s science landscape, an unspoken urgency and sincere passion shone through. Here is my summary of our conversation:

Conversation with Dr. Olivia Sanderfoot

Conversation with Dr. Olivia Sanderfoot After thanking Olivia for her time, I launched right into the “burning” question from our internet research: Should my kids and I worry about the birds in the current wildfire smoke? We were not sure because wildfires have occurred for as long as birds have been on the planet. If wildfires are a natural occurrence, have birds adapted? As some say, are the recent fires good because they create new habitats? Canaries were trapped in cages in mines, but wild birds are free to flee.

What I learned from Olivia:

Fire is a natural phenomenon. It has shaped landscapes for millions of years. Wildlife has evolved and adapted to historical wildfires. In some areas, frequent low-severity and infrequent high-severity fires are defining characteristics of local ecosystems. For example, some plant and animal species depend on burns. There are plants with sealed seeds that are released by wildfire heat. Some birds, like certain woodpeckers, thrive in burned habitats, where they harvest insects from charred snags.

However, global wildfire activity is intensifying, and wildfires in the U.S. have increased in frequency, intensity, and severity. “Megafires” – those greater than 10,000 acres – are becoming more common. Modern wildfires are faster, longer lasting, and cover greater areas. With more energy, they also consume more vegetation. The primary reasons for these “Megafires” are fire suppression and climate change combined. Fire suppression has caused more undergrowth accumulation. Previously, frequent low-severity fires would clear out understory fuels like downed branches and flammable shrubs. Climate change has led to higher temperatures for longer durations which dries out the understory, and other forest fuels, in turn creating more dry kindle. More flammable understory and drier materials and vegetation at all levels of the forest system make larger, mature trees and plants more vulnerable to damage from fires. While a tall, mature ponderosa pine may live through a low-severity fire, it may not survive a megafire.

Fires are occurring more frequently, both earlier and later in the year. Fire “seasons” of greater duration may create new challenges for birds that are not used to migrating through active wildfire areas.

Dr. Sanderfoot

Olivia is a UCLA Postdoctoral Scholar with a Ph.D. from the University of Washington . Her B.S. in Biology and Spanish and M.S. in environmental science are from the University of Wisconsin. Here is a link to her CV: https://ovsanderfoot.com/curiculum-vitae/

Here is a link to Olivia’s research page: https://ovsanderfoot.com/research/. Her research has focused on the effects of air pollution, such as wildfire smoke, and birds. Olivia has been interviewed about her research by National Geographic, Discover Magazine, Audubon Magazine, Popular Science, The Seattle Times, The Washington Post, and local radio and TV stations.

Smoke can be a cue for birds and animals. Historically, birds and animals may have reacted to smoke in ways that increased their chances of survival. The sight and odor of smoke can trigger an instinct to avoid fire danger. Interestingly, some predators may take advantage of wildfire smoke by preying on fleeing and injured animals on the edge of fires. During fires, birds may be able to escape to places outside the burn perimeter that is unaffected by the smoke.

Megafires create larger-scale smoke events. Plus, there are far fewer intact ecosystems to which to escape and use as alternative habitats during and after a fire. The question is how birds are impacted by these extensive and longer-lasting smoke periods with fewer available habitats. Are birds’ adaptations to historical fires sufficient? Can birds adapt to the new fire patterns?

Birds are highly vulnerable to air pollution, like the toxic gasses in smoke, because of how they breathe. When flying, birds have a huge need for oxygen. So they have evolved the most efficient respiratory system of all vertebrates. Essentially, birds constantly breathe in. They have relatively small lungs but nine (usually) large air sacs. These air-storing sacs mean air flows continuously in one direction through the birds’ lungs. When a bird inhales, the largest sacs around the abdomen fill with fresh air while pushing air from the last inhale into the lungs. When the bird exhales, the abdominal sacs again push air into the lungs. Before being released from the body, smaller air sacs nearer the throat store and release carbon dioxide from the lungs.

We do not fully understand how birds manage particulates in the air (i.e. the tiny bits of matter in the air like dust). They have a cough-like action, but it may not be as effective as a human cough for clearing debris because birds have longer, more rigid, and sometimes tightly coiled tracheas. Birds also do not have the same powerful immune system cells in their throats that mammals use to screen out most airborne threats. In addition, more research is needed to know whether birds can clear out dangerous airborne elements with a mucus system. Birds, compared to mammals, have a thinner barrier between blood and gas, which may cause them to absorb fine particulates more easily. For these physical reasons, while more study is needed, birds are highly likely to be more vulnerable than other animals to the health issues caused by inhaling the particulate matter in smoke and other kinds of air pollution. Certainly, smoke impacts bird health, but we still need to understand precisely how, to what extent, and does susceptibility vary by species, age, and sex.

YouTube videos on avian respiration:

There are relatively few published studies providing scientific data on how wildfire smoke impacts the health of wild birds and their populations – or any other taxa of wildlife, for that matter. In an international database of scientific papers, Sanderfoot and her team found that only six studies have directly examined birds and smoke. None provides a detailed examination of a species resident to the Northwest. One study investigated the impacts of smoke on a goose species that migrates through the Northwest, including a stop at Summer Lake in Central Oregon.

There are approximately forty-one studies on how wildfire smoke impacts animals. Some of that data is useful when developing theories on how severe fires impact Western U.S. birds. Taken together, the animal studies, some of which focused on livestock or animals from other areas, like Indonesian Hornbills and Cuban Parrots, indicate that smoke from megafires is highly likely to negatively impact many of our wild bird species, both in regard to individual health and population numbers.

Olivia and her team are working to understand better the impacts of wildfire smoke on wild birds and their causes, so they can contribute this data to the strategies and decisions addressing Western U.S. megafires.

While Olivia was not involved in the migrating goose research referenced in her team’s overview paper, she points to it as an interesting example of a recent study investigating smoke impacts on birds. Here is a link to the goose study: https://esajournals.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/ecy.3552. This study looked at how wildfire smoke may have impacted the migration of four Tule Greater White-fronted Geese (Anser albifrons elgasi). The tules usually migrate from Alaska through British Columbia and Washington State, then down to Summer Lake, Oregon, for a stopover before heading south to winter in California.

In 2020, there were areas of thick wildfire smoke along the tule’s typical migration route through Canada and Washington. Scientists tracked four tules with GPS collars to observe how they responded to the dense smoke on their route. The research showed the geese flew further and traveled longer when heavy smoke was on their route. Wildfire smoke seemed to cause the geese to stop, change direction, alter behaviors, and fly at different heights than usual.

Here is an excerpt regarding the extent of the wildfire smoke in the Pacific Northwest migration areas for the 2020 study: “We observed impacts to individual migratory behavior at smoke concentrations averaging 161 µgm−3. At ground surface elevations, smoke concentrations exceeded this threshold across a geographic extent 27 times greater than the area burned by wildfires. However, at observed migration altitudes (<4,000m), this smoke concentration covered an area 44 times larger than the wildfires themselves, encompassing 64% of four western states (California, Nevada, Oregon, and Washington) and effectively transecting the Pacific Flyway.”

Migration delays and challenges can be fatal. Migration is when birds use the most energy. Birds evolved sophisticated strategies to survive these grueling journeys, including timing and routes designed to conserve and replenish critical energy supplies. Even minor interruptions can have devastating impacts. The tule study authors note that “continuing reductions in wetland extent within the Northern Great Basin” already make it harder for migrating waterfowl to find quality resting and refueling stops.

The four tule geese experienced significant issues in 2020. To avoid smoke, one tule ended up separating from the flock and prevailing winds took it to Idaho where it was the first confirmed tule ever to visit that state. Several of the geese floated for up to 72 hours on the Pacific, waiting for the smoke to clear. Those that tried flying over smoke plumes had to climb to higher altitudes in flocks that became disorganized and dispersed to atypical migration habitats. While all four tules finally made it to Summer Lake, on average they used up four times the energy and traveled over 470 miles further than usual. Their trips were more than double a tule’s average migration duration.

The amount of extra energy these tules expended to get to Summer Lake in 2020 could result in a need to feed for an additional four to six days to survive the migration. Significantly, the study states: “Energy deficits such as we describe, especially when occurring in the context of incomplete knowledge of available food resource locations, can lead to increased mortality or reproductive rates insufficient to maintain goose populations (Klaasen et al. 2005).”

The tule study is a single look at four geese for one migration during a historic smoke event. This research may be limited, but at a minimum, it points to a time-sensitive need for more information. Wildfires and associated smoke pollution may pose a serious compounding threat when U.S. bird populations are already declining at a rate considered by many ornithologists as highly concerning.

The other forty relevant animal studies find some smoke-related harm, including impacts on vital rates, such as survival and reproduction. Olivia and her team compiled this information in a literature review published in Environmental Research Letters in January. (https://iopscience.iop.org/article/10.1088/1748-9326/ac30f6). Her team concluded: “Although studies that directly investigated effects of smoke on wildlife were few in number, they show that wildfire smoke contributes to adverse acute and chronic health outcomes in wildlife and influences animal behavior.”

Running out of time to talk, I asked Olivia a final question. Inspired by my desire to end on a hopeful note and being a parent wanting a positive future for my kids, I need action items our family can take to help the Sunriver area birds we love and enjoy. So I asked Olivia what, other than supporting research efforts like hers, we can do to address the increasing smoke issues facing birds in our area.

My summary of Olivia’s response:

Fire suppression is a contributing factor to increased wildfire activity, so it will be important to execute carefully planned and managed prescribed burns or other safe and wildlife-friendly understory reduction efforts. There are many questions and caveats to consider when planning controlled burns and forest thinning, but these efforts may be necessary. These measures should be conducted in ways that enhance rather than degrade ecosystems.

Greenhouse gases contribute to the temperature increases that dry forest fuels. So, we can all consider ways to decrease those emissions on the personal and policy levels.

When birds face smoke event stressors, they need habitats where they can build up their strength before fires and where they can recover after the burn. These include safe places to forage, rest, and perhaps relocate and live if their habitat was destroyed by fire. Bird-friendly habitats include native plants and animals, clean water, and food sources. These habitats could be in your garden, common areas, or land over which you have some control. Consider volunteering to help create bird-friendly habitats on public land and private areas being restored or managed by conservation groups.

When birds’ systems are compromised by smoke inhalation, they may be susceptible to more serious health issues if they are exposed to toxic forms of pesticides, herbicides, fertilizers, and poisonous substances like lead. So, consider non-toxic ways to manage land and pests.

If you have bird feeders and baths, make sure they are clean. Birds sickened by smoke inhalation may better survive if they do not pick up a virus or bacteria. Watch for local notices about bird diseases and follow guidelines to prevent more cases.

Citizen science helps researchers. Contribute by submitting eBird lists before, during, and after smoke events. Consider adding the AQI or a note about recent or nearby smoke areas to your comment section and the weather conditions. Of course, when birding, you should follow fire and smoke closure rules and health advisories.

Have your local bird rescue and care contact information on hand during smoke events. You may encounter birds impacted by smoke inhalation or fire. Consider seeking expert advice on how to address bird injuries and illness.

I thanked Olivia for her important work, kindness, and commitment to public education.

She provided several links to relevant talks for those interested in learning more:

Recent talks:

Recent news stories and related research: https://ovsanderfoot.com/news/