By Sevilla Rhoads

Special thank you to Chuck Gates for reviewing this post.

Owls of the Upper Deschutes

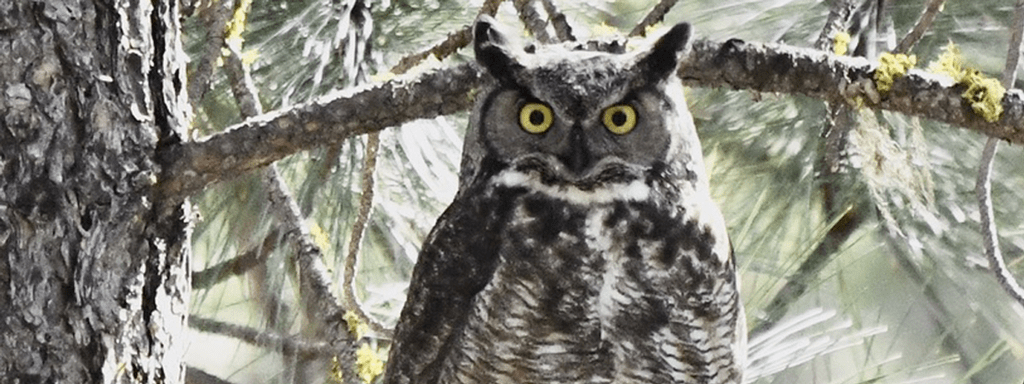

Part One: The Great Horned Owl (bubo virginianus)

Noah Strycker’s Birding Without Borders starts: “On New Year’s Day, superstitious birdwatchers like to say, the very first bird you see is an omen for the future.” Predawn on January 1, 2023, the snowy Upper Deschutes’ forests and meadows were mostly quiet to the human ear. Most of us, except perhaps some intrepid hunters, were snuggled in bed.

Suddenly, around 4 a.m., a primal alarm clock roused us with a deep hooting. A Great Horned Owl pushed the winter’s silence out of the shadowy conifers into the barely-moonlit river valley. Like its deep blanket of down, the owl’s call is thick and full. The first hoot was soon answered by another in the distance. Then the owls performed a duet with voices perfectly evolved to carry through snow-coated landscapes of ice-draped trees.

For those of us urged by Great Horned Owls to start 2023 early, we wonder what this species portends?

The Klamath-Modoc people (who lived mostly to the south, but spent time in the Upper Deschutes) have references to an Owl Spirit called ‘Mukus’ or ‘mu’lwas’. It is thought Mukus helped Klamath healers diagnose illness. One translation of a Klamath doctor’s incantation is: “I possess the horned owl’s sharp vision…”. An ancient rock illustration in the Klamath area depicts a Great Horned Owl’s face high on the rock wall. At least one scholar thinks this image refers to the owl helping a Shaman see illness from a high perch.

However, for some Klamath, healing is not the only association with Great Horned Owls. In one ancient creation story, an “evil” force created the Great Horned Owl. A dark power, jealous of the original creator, gave the Great Horned Owl fierce and deadly traits such as silent flight.

Some Klamath tribal members (often young men, older women, and those called to Shamanism) likely engaged in vision quests. Alone on their quests, in places like the Upper Deschutes, they fasted and plunged into cold waters while waiting for guidance in visions. Some believed the first vision would be the Great Horned Owl who would tempt with these words: “My eyes look like the Sun and I can see anything, here, far away, or even in the future. This is why nothing can hide from me. And I am strong; I can kill anything with my claws. I am a good hunter and warrior; I am silent and can sneak up on anything and kill it without it noticing me. This is what I do, so if you really want power, then take me.” From The Landscape of Klamath Basin Rock Art. [http://npshistory.com/publications/labe/klamath-basin-rock-art.pdf]

There are “horned” owls in many other areas, including Eurasia. One example is the large Eurasian Eagle Owl. Interestingly, some Christian traditions depict Jesus being tempted by a horned being during his “vision quest” in the wilderness. Also, several ancient European myths, including some original Christmas stories, have descriptions of dark-horned beings punishing naughty children on winter nights. If you are now curious what an Eurasian Eagle Owl looks like, there is one at the Sunriver Nature Center.

“Hoo” knows whether large nocturnal owls played any role in the development of these stories. But, as the Great Horned Owl keeps you awake during our own long mid-winter nights, it is fun to wonder if and why tufted owls touched the diverse imaginations of ancestors in similar ways. What we do know is that there is a high chance the early January Great Horned Owl calls have woken the people of the Upper Deschutes for thousands of years.

“Hoo” knows whether large nocturnal owls played any role in the development of these stories. But, as the Great Horned Owl keeps you awake during our own long mid-winter nights, it is fun to wonder if and why tufted owls touched the diverse imaginations of ancestors in similar ways. What we do know is that there is a high chance the early January Great Horned Owl calls have woken the people of the Upper Deschutes for thousands of years.

Having just read about the Klamath’s idea of Mukus as a healing spirit, I was struck by a story in Jim Anderson’s autobiography, Tales from a Northwest Naturalist. In his book, Jim Anderson, a founder of the Sunriver Nature Center’s nature programs, wrote a moving account of a nature talk he gave to a special education class. During his class presentation with a live Great Horned Owl, Jim noticed a girl pacing silently staring at the owl. After the presentation, as Jim went to leave, the young girl blocked his way out. Suddenly, she said “I know about owls!” and then talked excitedly at length with a smile that “lit up the room.” Afterwards, Jim was stopped at his car by a teacher, with tears in her eyes, who said “that’s the first time that child has spoken since she has been in this school.” Jim reflected “That owl had found a key – a path for a young girl to take…” p.137. Jim Anderson, who passed in 2022, said his favorite animal was the Great Horned Owl. So, it is not surprising that his book is full of wonderful Great Horned Owl stories and information and is a great read for anyone sharing his passion for this bird.

Back to January 2023, I noticed that, as the moon grew fuller, the Great Horned Owls’ calls became more insistent. By the full moon, the owls barely waited until dark to start calling. By the February 5th full moon, their hoots were shooing the late afternoon light to retreat more quickly behind the Cascades so they could perform their courting and territorial grand finales. Early February sunsets in the Upper Deschutes are stage lighting for Great Horned Owl operas.

Like other owl species, Great Horned Owls breed in the winter. Around Sunriver, these owls start calling to each other in mid to late December and likely nest in mid to late February. They cannot build nests, so they find ones built by raptors, ravens, and even squirrels and eagles. These nests can be in trees, platforms, cliffs, or any suitable surface. Sometimes the original nest owner will still be around, especially the Red-tailed Hawks and Common Ravens. So pay attention if you see these species acting agitated around late January and February. In Sunriver, where several pairs of Great Horned Owls regularly nest, we have encountered some stand-offs between hawks, ravens, and owls. The powerful and confident Great Horned usually wins.

After laying around 1-4 eggs, the female incubates for roughly a month while the male brings her food. Imagine sitting on a pile of sticks through the weather we usually experience in February and March, such as those bitterly cold nights and driving snow storms! One late February, all we could see of a devoted owl mother were her tufts blown backward into her nest wall by a hard icy wind. Incubating females can keep their eggs warm even when temperatures are seventy degrees under the needed 37°.

While not often observed, there are documented owl families where two females incubated eggs and raised young together while a male fed them both. For example, see [https://www.nationalgeographic.com/animals/article/animals-owls-birds-parenting-polygamy] Also, female Great Horned Owls are larger than males. Jim Anderson’s book has some great photographs illustrating this gender size difference. Sometimes, birds help us question assumptions.

Just as flycatchers begin returning to South Deschutes County’s meadows in late April, we start to notice Great Horned Owl fledglings, sporting motley teenage molts, clumsily flying around. Usually, vigilant parents are close by. Around Sunriver, we have watched Great Horned Owl adults aggressively protect their loud floundering young as an unkindness of Common Ravens tries to carry off a fledgling.

Just as flycatchers begin returning to South Deschutes County’s meadows in late April, we start to notice Great Horned Owl fledglings, sporting motley teenage molts, clumsily flying around. Usually, vigilant parents are close by. Around Sunriver, we have watched Great Horned Owl adults aggressively protect their loud floundering young as an unkindness of Common Ravens tries to carry off a fledgling.

Great Horned Owls are powerful. Depending on which study you read, a mature female’s talons can exert between 500 to 750 PSI of pressure. This degree of talon strength allows Great Horned Owls to prey on a wide variety of animals and even other birds of prey, some of which are bigger than the owl itself. [https://sora.unm.edu/sites/default/files/journals/jrr/v036n01/p00058-p00065.pdf] Highly adaptable, the Great Horned will eat a surprising range of creatures, including reptiles, other owls, and skunks. In an excellent December 2022 Bend Source article by Damian Fagan, he provides information from Think Wild about how most of their Great Horned Owl patients arrive smelling strongly of skunk! [https://www.bendsource.com/outside/species-spotlight-great-horned-owl-18266497] Adapted to urban life, Great Horned Owls also eat pets. Near one Pacific Northwest town, an abandoned Great Horned Owl nest was found to contain some cat collars whose bells had inadvertently advertised dinner for the Great Horned.

If you have ever watched a Great Horned Owl eat its catch, you may have noticed that if the prey fits, it goes down whole – head, body, fur, feet, and lastly, the tail, disappear without a single chew! Owls cannot chew and do not have teeth. They can tear prey into smaller pieces, but the preferred dining experience is a whole meal deal. As you can imagine, all those bones are hard to digest. The owl’s gizzard separates the digestible soft tissues and packages the teeth, bones, and feathers into a regurgitated pellet. Owl pellets are infamous aspects of many a kid nature camp or science class because you can often find the entire skeletons to recreate the owl’s last victims.

Native to the U.S., Great Horned Owls are widespread. They are one of our remaining native predators, in part because they have adapted well to human development. The owls’ success is a mixed blessing. It is wonderful we can listen to the call of an owl depicted in the local ancient myths, but Great Horned Owls are aggressive predators who know how to take advantage of less adaptive species. Pushed into smaller wild spaces by development, fires, droughts, and other factors, some animals have fewer places to hide from the Great Horned and more easily become prey. For example, the Great Horned Owl is one of the primary predators of the uncommon Great Gray Owls.

On the positive side, recent scientific studies emphasize the significant benefits of having apex (top) predators in habitats. [Https://tesf.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/08/Ripple-etal_2022.pdf] Top predators help keep prey populations, like rodents, to naturally healthy numbers, which helps the plants and other animals impacted by the overpopulation of any species. A more balanced natural environment leads to fewer fires, droughts, and diseases, not to mention the increased natural beauty of our precious and unique Upper Deschutes area.

Speaking of apex predators, there is ample documentation of communication between wolves and ravens, but another possible inter-species conversation is between Great Horned Owls and wolves. We know little about how Oregon’s native wolves interacted with other native predators in the Upper Deschutes because wolves were exterminated from this area by 1947, but a recent study of Yellowstone area recordings indicated an intentional communication between Great Horned Owls and howling wolves.

[https://www.npca.org/articles/3168-are-you-talking-to-me] It is possible wolves will repopulate the Upper Deschutes, so perhaps one day we will be fortunate enough to hear a nocturnal duet between owls and wolves.

Great Horned Owls do not migrate, so we enjoy them year round here in south Deschutes County. Being one of the most adaptable species, their population is not currently threatened. These owls are a welcome source of free pest control in this area. One of their favorite snacks are rodents and they greatly help reduce rodent populations around our homes and businesses. However, many owls die from ingesting rodent bait because the poisoned rats and mice are easy prey, especially in the winter and when the owls are trying to feed hungry kids back in the nest. So, if you see or hear owls in your neighborhood, consider non-poison pest control methods, especially during the winter and spring.

Great Horned Owls do not migrate, so we enjoy them year round here in south Deschutes County. Being one of the most adaptable species, their population is not currently threatened. These owls are a welcome source of free pest control in this area. One of their favorite snacks are rodents and they greatly help reduce rodent populations around our homes and businesses. However, many owls die from ingesting rodent bait because the poisoned rats and mice are easy prey, especially in the winter and when the owls are trying to feed hungry kids back in the nest. So, if you see or hear owls in your neighborhood, consider non-poison pest control methods, especially during the winter and spring.

For a great source of further identification tips, call sounds and species information, see:

https://www.allaboutbirds.org/guide/Great_Horned_Owl/overview