At four in the morning on December 20th, the Sunriver forest was so quiet, you could hear the light snow patting the frozen trees. It was just above freezing. Suddenly, startlingly close, a deep hoot pushed through the silence. This was the bugle sounding the start of the Sunriver 2022 Bird Count. Species number one: Great Horned Owl.

By sunrise, volunteer birders had three Great Horned Owls on our list. As these owls closed their eyes to roost for the day, around fifty Bird Count volunteers were setting out, bundled up (many with coffee in hand), to start their routes. Their mission: As part of the 123rd Audubon ‘Christmas’ Bird Count, to spot and identify on one day, as many birds as possible in a fifteen mile diameter circle around the Sunriver area.

Sunriver’s Circle includes the frozen waterfalls of Fall River, the gurgling of never frozen springs at Spring River, the icy slopes of Lava Butte, golf courses turned winter tundras such as Crosswater and Quail Run, rarely visited snow-encased buttes west and south of Edison Ice Cave Road including Kuamaski and Wake, the feeders and neighborhoods of Sunriver and Three Rivers, and the Deschutes river trails across from the lava flows at Dillon Falls all the way down to where the river flows into La Pine State Park.

The majority of volunteers were beginners, willing to help scour trees and skylines to find birds for their experienced team leaders to identify and record. Volunteer ages ranged from nine to around ninety. Some teams took all-wheel drive high clearance vehicles down forest service roads, some hiked with traction boots and poles along the icy river trails and there was a stationary count at the Sunriver Nature Center, where people could equally contribute in a more accessible location, by watching the critical lake and meadow habitats.

In addition to finding over 3,923 individual birds in one day, volunteers also made new friends, learned from each other, had a lot of fun, experienced beauty and the joy of nature, and meaningfully contributed to citizen science.

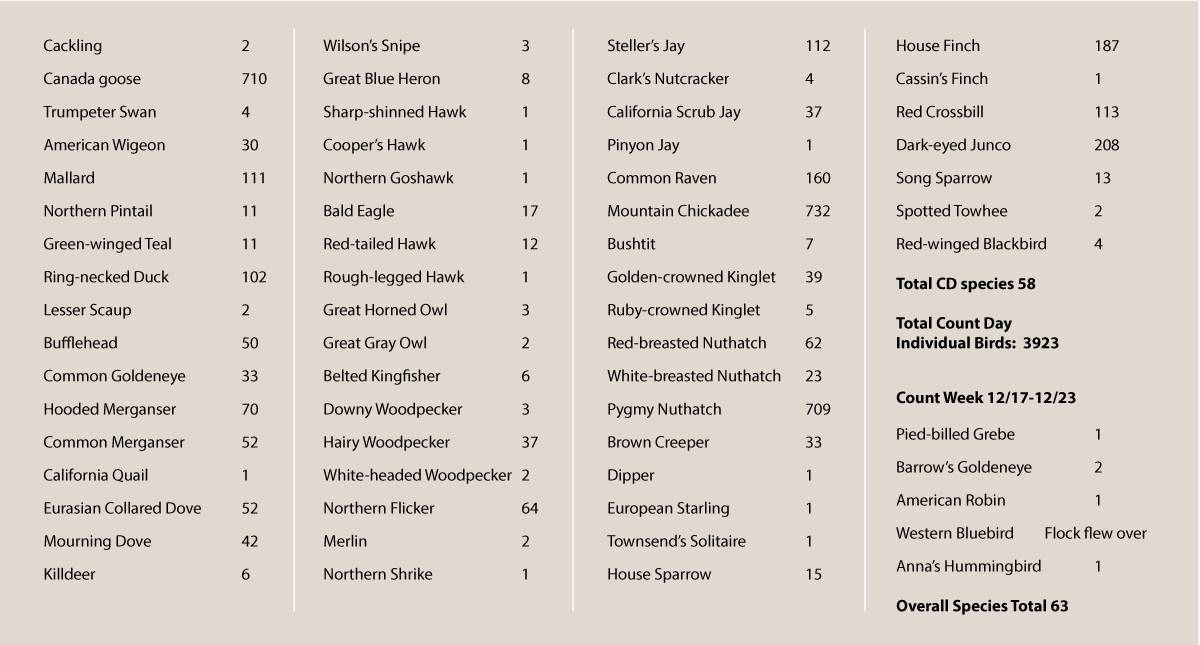

Despite many frozen waterways, deep snow cover, and recent below zero temperatures, these volunteers were able to confirm 58 bird species.

Some highlights of the day:

- A family in the community welcomed a team of birders into their yard where they caught a good look at a very unusual Pinyon Jay.

- A couple in their off-road truck discovered an American Dipper foraging on Fall River.

- Nature Center bird walk leaders recorded four wild Trumpeter Swans by Cardinal Bridge.

- The La Pine State Park team was thrilled to spot the elusive Northern Goshawk.

- The Nature Center team, after being delighted by a flock of Pygmy Nuthatches emerging from a tree cavity, spied a Rough-legged Hawk which is an arctic breeding species. A visiting teenager at the Nature Center, there to practice his nature photography hobby, was able to help identify the Hawk by showing the birders a close-up on his camera of the bird’s markings.

- A kid found a Great Gray Owl and was able to take a great photo with his parent’s iPhone.

- A group of mostly beginners, as part of the twenty-one species on their list, enjoyed watching a Merlin hunting by the river as well as seeing two Bald Eagles on their route.

- One river trail team found themselves looking for ducks alongside a group of hunters. The hunters and birders talked of their shared interest in conserving natural beauty and future bird populations and the hunters asked for more information about how they could join a Nature Center team next year to help with the effort.

- Thanks in large part to the residential area team (who had to dig their hybrid out of a snow bank more than once during the count process), our final bird list included over seven hundred Pygmy Nuthatches and over seven hundred Mountain Chickadees! Many volunteer smiles were inspired by seeing so many cute little fluffs in just one day!

On Count Day evening, teams were able to share these and many more stories as they warmed up at the Nature Center with volunteer donated hot cocoa and cookies. The count ended around 9pm with one last determined volunteer sloshing around looking for owls in the snow-turned-rain.

The final count numbers as seen below will be available on Audubon’s CBC site after the official tally is approved.

We are already planning the 2023 Count! It will again be on December 20th with the same Circle area.

Audubon’s Participation Mission Statement:

“Protecting and conserving nature and the environment transcends political, cultural, and social boundaries. Respect, inclusion, and opportunity for people of all backgrounds, lifestyles, perspectives, and abilities will attract the best ideas and harness the greatest passion to shape a healthier, more vibrant future for all of us who share our planet. We welcome everyone who finds delight in birds and nature. Participation in the Audubon Christmas Bird Count brings us together as a caring community of people who are inspired by birds and want to protect them.”

2022 Totals

Photos: Sevilla Rhoads

Large piercing orange eyes. A 6 foot wingspan. 10 pounds of muscle, bone, and feathers. Prominent ear tufts. And no natural predators. Meet Sunriver Nature Center & Observatory’s (SNCO) newest animal ambassador – a Eurasian Eagle-owl (Bubo bubo). At just two months old, however, the yet-to-be-named female owlet, is still very much fluff and only beginning to learn how to fly.

Large piercing orange eyes. A 6 foot wingspan. 10 pounds of muscle, bone, and feathers. Prominent ear tufts. And no natural predators. Meet Sunriver Nature Center & Observatory’s (SNCO) newest animal ambassador – a Eurasian Eagle-owl (Bubo bubo). At just two months old, however, the yet-to-be-named female owlet, is still very much fluff and only beginning to learn how to fly. Over the next few months, the owl will be learning all about its environment, carefully guided by her caretakers. At this age, exposure to many different sights, sounds, people, and places will help her prepare for just about anything she may encounter in her role as an ambassador of bird conservation at SNCO. As she learns to fly, we will introduce training sessions to her daily routine. These training sessions, based in positive reinforcement, will foster a long-term trusting relationship with her caretakers and give her the ability to make choices in her environment. Training behaviors such as voluntarily stepping on a scale, or lifting a foot up to be examined, will also help her caretakers and veterinarian monitor her health in a minimally invasive way without force. For now, the SNCO team is enjoying getting to know our newest co-worker. We have discovered that she loves shredding old issues of the Sunriver Scene. She takes long naps in the most surprising of ways – flat on her stomach with her legs stretched behind her. She is starting to explore new foods, though mice remain her favorite so far. And she’s met numerous families during our weekly animal storytime. The owl does not have a name however, so we are asking for suggestions from her peers – children. You can submit a name online at:

Over the next few months, the owl will be learning all about its environment, carefully guided by her caretakers. At this age, exposure to many different sights, sounds, people, and places will help her prepare for just about anything she may encounter in her role as an ambassador of bird conservation at SNCO. As she learns to fly, we will introduce training sessions to her daily routine. These training sessions, based in positive reinforcement, will foster a long-term trusting relationship with her caretakers and give her the ability to make choices in her environment. Training behaviors such as voluntarily stepping on a scale, or lifting a foot up to be examined, will also help her caretakers and veterinarian monitor her health in a minimally invasive way without force. For now, the SNCO team is enjoying getting to know our newest co-worker. We have discovered that she loves shredding old issues of the Sunriver Scene. She takes long naps in the most surprising of ways – flat on her stomach with her legs stretched behind her. She is starting to explore new foods, though mice remain her favorite so far. And she’s met numerous families during our weekly animal storytime. The owl does not have a name however, so we are asking for suggestions from her peers – children. You can submit a name online at: