Golden-crowned Kinglet Ruby-crowned Kinglet

Royal Fluff: Kinglets of the Upper Deschutes

by Sevilla Rhoads

Regulus satrapa and Corthylio calendula

Ruby-crowned Kinglet

Golden-crowned Kinglet

When you see royal terms like ‘king’ and ‘crowned’ in a bird’s name, you might imagine some majestic creature akin to a heron or bird of prey. However, the Golden-crowned (Regulus satrapa) and Ruby-crowned Kinglets (Corthylio calendula) are miniature, supremely adorable songbirds. These mini-cotton ball birds almost define cuteness and perhaps also hope….every winter day, kinglets tragically live on the edge of death. Just enough of them survive to replenish the population during the summer.

Ruby-crowned Kinglet

Over ninety percent of kinglets die during the colder months. One night of adverse weather can wipe out entire flocks. Kinglets who survive as long as our April thaw here in Sunriver and La Pine, are the few which have defied the odds to feel the warmth of the spring sunshine. It is still largely a mystery how they survive at all. Scientist and naturalist author, Bernd Heinrich is “awestruck by” and “marvels at” Golden-crowned Kinglets in his book Winter World. He concludes the book by saying they “prove the fabulous is possible.”

Kinglets are one of the rewards for Upper Deschutes’ winter birding. Rarely seen around Sunriver and La Pine in the summer, during the winter flocks regularly flit and forage around this area. In early April, those that survived winter will head north to nest. Some remain in the Upper Deschutes, but at higher elevations in places with more fir trees, such as around Brown’s Mountain. It is not clear if any breed here.

While barely known by the general public, kinglets deeply move those who come to know them. One of America’s foremost ornithologists, Arthur Bent, began his love of birds when he found a dead kinglet (a “tiny feathered gem”) whose delicate delightful details sparked a life of avian interest.

Golden-crowned in flight

Golden-crowned has deep layer of insulating feathers

Golden-crowned fluff can interfere with speed and agility

Kinglets typically weigh only five to six grams (less than half an ounce or about the weight of a nickel). They are among the world’s smallest songbirds. The Golden-crowned (the smaller of the two Kinglets) is barely bigger than a hummingbird. And, much of their size is truly just fluff.

Living in cold climates, they have more insulation than flight feathers. To stay warm, they trap as much air as they can between feathers, which gives them their round seeding-dandelion look. While their down gives these birds their sweet stuffed animal look, it also slows them down in flight, making them more vulnerable to predators. Perhaps their slower aerial turning speed is a reason kinglets are one of the birds most frequently killed by window strikes.

Barely bigger than a pine cone size allows feeding where bigger birds cannot reach

Golden-crowned hovering to feed

Being so small, Golden-crowned Kinglets are well adapted to hanging off the tips of pine needles to get the almost microscopic insects that larger birds cannot see or reach. The Golden-crowned often hovers, almost like a puffy hummingbird, when they glean. Before Heinrich questioned the assumption, it was thought Golden-crowned survived the winters by eating Springtails. Springtails (sometimes called Snow Fleas, even though they do not bite) are those tiny bugs that appear like thousands of black dots on the snow. https://www.

Rarely seen at feeders, a Ruby-crowned makes an exception for a particularly cold day

Ruby-crowned are a bit bigger but also mostly eat insects. They are known for wing-flicking during foraging, which some believe is a way to scare bugs out of hiding. We don’t see why an insect would reveal itself when a bird flicks its wings, but we can’t think of a better theory!

Ruby-crowned are a bit bigger but also mostly eat insects. They are known for wing-flicking during foraging, which some believe is a way to scare bugs out of hiding. We don’t see why an insect would reveal itself when a bird flicks its wings, but we can’t think of a better theory!

When you encounter a kinglet, you quickly notice its almost constant movement. Sometimes described as frantic, kinglets live in fast-forward mode. Ruby-crowned pause and appear in the open more often than Golden-crowned, but both species are incredibly energetic such that they literally vanish in the blink of an eye. Most of my kinglet photos are of disappearing fuzzy bottoms and feet! Even when I press the shutter when I see a kinglet, the bird has often moved on by the time my camera reacts.

Fluffy bottoms disappearing is how we often see both Golden-crowned and Ruby-crowned Kinglets!

Why are kinglets so busy? It is a matter of pure survival against the odds. Kinglets have to continually refuel in order to stay alive. Due, in part, to their size, they have to maintain a body temperature of around 104 degrees Fahrenheit. One study, cited by Cornell’s Birds of the World, stated the observed Golden-crowned Kinglets did not stop foraging, even once, during the day in winter. Heinrich estimated they move every two to four seconds. Imagine having to gather and eat food without interruption all day for months to stay alive.

On a cold day, Kinglets can starve and freeze to death in just one to two hours if they do not find enough food. Almost ninety percent of kinglets die in their first winter. They have on of the shortest lifespans in the bird world. Disruption to their habitat, such as a loss of crucial food sources and changes to the climate, can take a heavy toll on this species, with entire flocks dying during a night. Interestingly, it is slightly warmer temperatures producing cold rain in stead of snowflakes which may be most dangerous to kinglets because wet feathers cannot insulate sufficiently for a long freezing night.

A rain-drenched Golden-crowned trying to dry off after a storm.

You have to wonder why kinglets didn’t evolve to migrate further south like so many other little birds. They probably play some key role in our winter ecosystem, which we do not yet understand. There is some controversy among experts about how kinglets survive winter nights, especially the Golden-crowned, which have made it through northern winters with temperatures hitting lows of minus forty. One study found that, even when a Golden-crowned finds enough food during the day, it is only enough fat for half a night of life-sustaining metabolism.

You have to wonder why kinglets didn’t evolve to migrate further south like so many other little birds. They probably play some key role in our winter ecosystem, which we do not yet understand. There is some controversy among experts about how kinglets survive winter nights, especially the Golden-crowned, which have made it through northern winters with temperatures hitting lows of minus forty. One study found that, even when a Golden-crowned finds enough food during the day, it is only enough fat for half a night of life-sustaining metabolism.

In the book Winter World, Bernd Heinrich is “awestruck” Golden-crowned Kinglets survive more than five minutes on a cold winter day. Pointing out these birds need to maintain a temperature several degrees higher than most other creatures and often over a hundred degrees higher than the chilled air around it, Heinrich spent years figuring out how any kinglets make it to spring.

Unlike many other winter birds, Kinglets do not use torpor (which is a lite hibernation state used to get through cold snaps), so they must find enough food to get through the day and find shelter and warmth for the night. Before Heinrich’s dedicated observing, it was thought kinglets slept in insulated squirrel nests. However, squirrels eat birds like kinglets, and their nests are too well-sealed for a kinglet to break in. Heinrich concluded kinglets find shelter wherever they can, nearest the last good foraging (because they do not have time to stop eating to find or build shelters), then rely on huddling up together with feet and heads tucked in. He once found four kinglets sleeping in a ball with just tails sticking out. https://vtecostudies.org/

Heinrich also speculates that Golden-crowned Kinglets constantly call to each other because if you lose your friend during the day, you could all die that night. They need to huddle together in enough numbers to generate life-saving heat. Since reading this theory, I hear the kinglet’s constant tiny sounds so differently than before as I imagine them calling “I’m here!” to each other.

Not breeding in winter or around Sunriver and La Pine, the male orange crest is often flattened on Golden-crowned we see at this elevation

Male Golden-crowned showing orange crown feathers

Perhaps due to the high mortality rate, Golden-crowned Kinglets have two sets of kids a year and lay more eggs than most other songbirds (between 8 and 12 eggs per brood). They usually breed up in the northern boreal forests (some breed south of Canada) in such tiny nests that little is known about their family lives. Much of their summer is still a mystery to ornithologists, but it is thought that when the chicks fledge, the females tend to hand off the first set of kids to the male to look after while she focuses on laying another batch of eggs. Sometimes, Dad is expected to feed all ten or so chicks and Mum while she incubates the rest of the year’s youngsters. Golden-crowned Dads are superhero foragers for their families which can consist of over twenty-four kids at a time!

While kinglets have one of the highest adult death rates, they have one of the lowest chick mortality rates. The following information about a Golden-crowned nest is mostly from only a handful of observations. While the male sings supportive tunes (perhaps conserving his energy for his future father duties), the female builds an incredible nest to insulate and protect her eggs and newborns. Mainly using spider webs, she weaves a silken pouch under a branch. Hanging under a bough, the nest is protected from the last snowstorms of the year and is hard for predators to reach. The walls of her nest are over an inch and a half thick, lined with moss, fur, and grouse feathers. She places the grouse feathers quill downwards around the nest to create a beautiful circular fan around her family. The female lays so many eggs she has to layer them. When they hatch, the chicks are barely as large as a bumblebee.

An Upper Deschutes spider perhaps openly carrying an egg cocoon to entice nest-building kinglets and wrens?

A little more is known about the Ruby-crowned because, while most also nest in the northern forests, a number nest further south where they can be more easily studied. Ruby-crowned can also have up to twelve eggs but usually only have one brood a year. In our blog post about the Brown Creeper, we marveled at how the Creeper uses spider cocoons to make nests, feed young, and combat nest mites. Ruby-crowned Kinglets also use spider cocoons and webs to build nests, but have an additional reason: Spider silk is flexible, which means the nest stretches to accommodate the growing chicks! https://www.

While both the Ruby-crowned and Golden-crowned are called Kinglets, they are genetically quite different. You would think you could easily tell these birds apart by their different crown colors, but in the winter, they tend to keep the crowns flat against their heads, making them hard to see on these rapidly moving tiny birds. At a quick glance, kinglets have similar bodies and can be confused, but look at their differing facial markings.

For ID purposes, note the striped face on the Golden-crowned

Note the lack of facial stripes on the Ruby-crowned which instead has white in front and behind the eye

The Golden-crowned has black and white stripes, whereas the Ruby-crowned only has a white eye-ring. They also have very different calls. The Golden-crowned chirps are frequent and high-pitched, like the tinkling of a brook, but the Ruby-crowned is often silent until it utters a surprisingly loud rasp that reminds me of a wren’s call.

Golden-crowned calling

For more identification and additional call information, including recordings, see: https://www.

If you want to enjoy our local south Deschutes County kinglets before they depart, pause on your walks, listen for the tiny calls, and then look for movement. During winter, Golden-crowned are common along the Sunriver trails and surrounding forests, but you can easily miss these darting fluffs if you do not pay attention. Ruby-crowned are more likely seen at the start and then end of the winter season than during the colder, snowier mid-winters here.

Ruby-crowned flicking wings while foraging

A Golden-crowned which survived to April

When we wish our local kinglets farewell in the spring, be sure to wish them luck and perhaps a nod of gratitude for brightening our winter days because they are critical pest control for North America’s surviving forests. Kinglets are known to move into areas where insect infestations threaten the remaining trees. Their specialized pest control, reaching bugs that larger birds cannot and eating pest larvae, is a crucial component of our ecosystems’ natural defense.

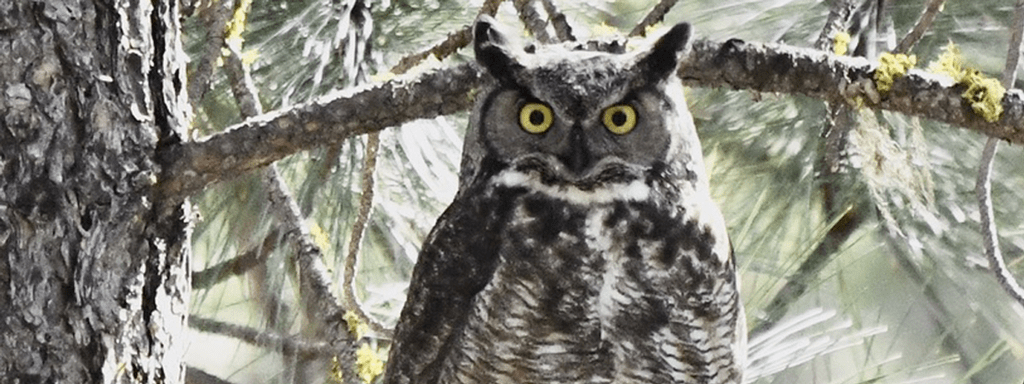

“Hoo” knows whether large nocturnal owls played any role in the development of these stories. But, as the Great Horned Owl keeps you awake during our own long mid-winter nights, it is fun to wonder if and why tufted owls touched the diverse imaginations of ancestors in similar ways. What we do know is that there is a high chance the early January Great Horned Owl calls have woken the people of the Upper Deschutes for thousands of years.

“Hoo” knows whether large nocturnal owls played any role in the development of these stories. But, as the Great Horned Owl keeps you awake during our own long mid-winter nights, it is fun to wonder if and why tufted owls touched the diverse imaginations of ancestors in similar ways. What we do know is that there is a high chance the early January Great Horned Owl calls have woken the people of the Upper Deschutes for thousands of years.

Just as flycatchers begin returning to South Deschutes County’s meadows in late April, we start to notice Great Horned Owl fledglings, sporting motley teenage molts, clumsily flying around.

Just as flycatchers begin returning to South Deschutes County’s meadows in late April, we start to notice Great Horned Owl fledglings, sporting motley teenage molts, clumsily flying around.

Great Horned Owls do not migrate, so we enjoy them year round here in south Deschutes County. Being one of the most adaptable species, their population is not currently threatened. These owls are a welcome source of free pest control in this area. One of their favorite snacks are rodents and they greatly help reduce rodent populations around our homes and businesses. However, many owls die from ingesting rodent bait because the poisoned rats and mice are easy prey, especially in the winter and when the owls are trying to feed hungry kids back in the nest. So, if you see or hear owls in your neighborhood, consider non-poison pest control methods, especially during the winter and spring.

Great Horned Owls do not migrate, so we enjoy them year round here in south Deschutes County. Being one of the most adaptable species, their population is not currently threatened. These owls are a welcome source of free pest control in this area. One of their favorite snacks are rodents and they greatly help reduce rodent populations around our homes and businesses. However, many owls die from ingesting rodent bait because the poisoned rats and mice are easy prey, especially in the winter and when the owls are trying to feed hungry kids back in the nest. So, if you see or hear owls in your neighborhood, consider non-poison pest control methods, especially during the winter and spring.

The scientific name for Eurasian Collared-Doves is Streptopelia decaocto. The second half of this name relates to an ancient Greek myth about call of this species: A maid was angry she worked too hard for only eighteen coins, so she begged the gods to tell the world how little her mistress paid her. Hearing her plea, Zeus created Collared-Doves to forever call out “Deca-octo” which means eighteen coins.

The scientific name for Eurasian Collared-Doves is Streptopelia decaocto. The second half of this name relates to an ancient Greek myth about call of this species: A maid was angry she worked too hard for only eighteen coins, so she begged the gods to tell the world how little her mistress paid her. Hearing her plea, Zeus created Collared-Doves to forever call out “Deca-octo” which means eighteen coins.